Now what?"

It's been a challenging year as new data have confirmed, with greater clarity, the distance left to go in addressing global and local HIV epidemics.

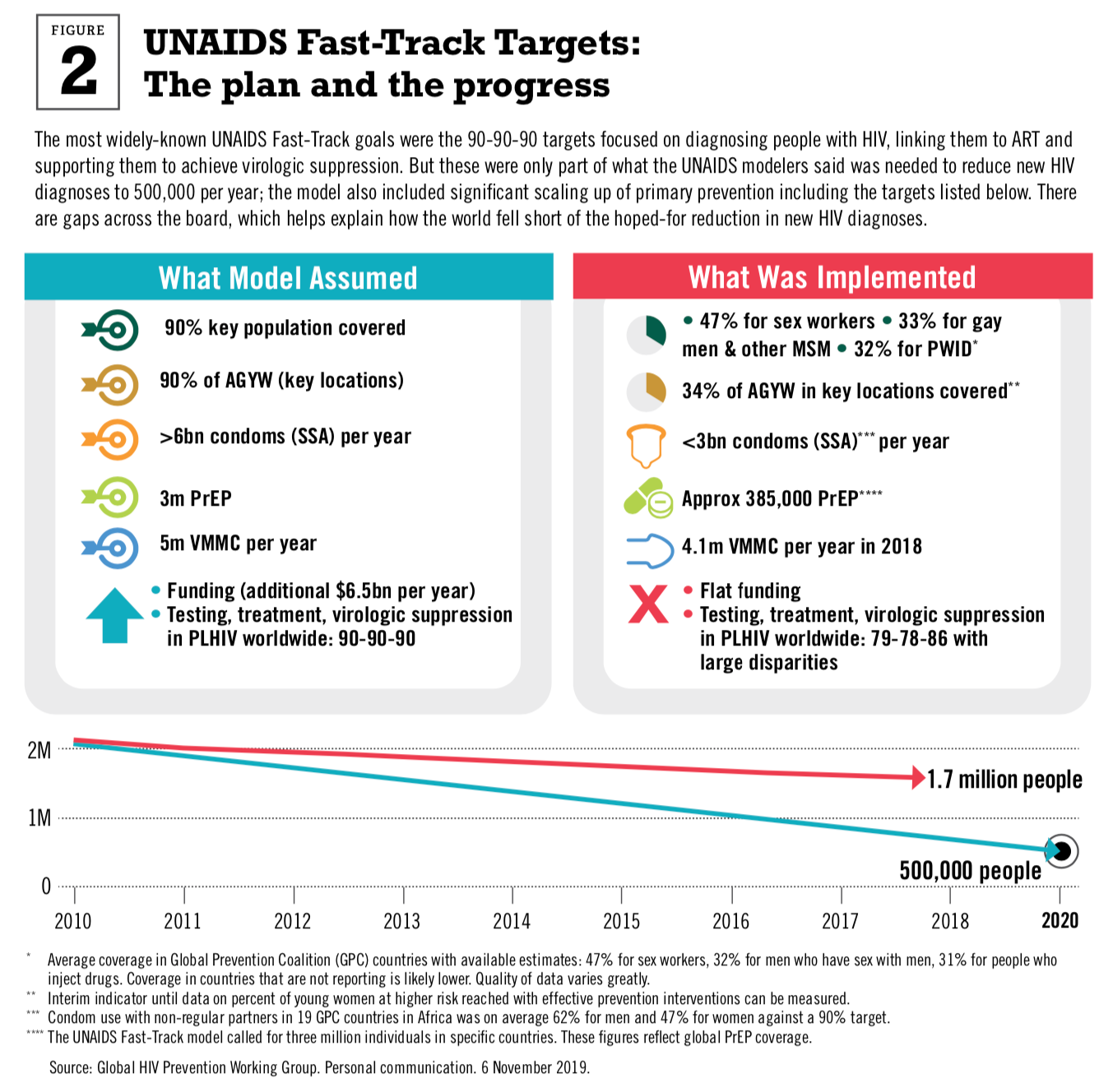

Midway through 2019, a range of trials brought new data on the potential and limitations of biomedical strategies in the global HIV response. The data weren't surprising, but they made some serious obstacles clearer than they have been before. Community-wide testing followed by ART for people living with HIV has health benefits for the individual and reduces incidence by around 30 percent. That's both invaluable and insufficient to end epidemic levels of new diagnoses. 2019 also brought fresh data from the ECHO trial, data on HIV risk in young women, and their unmet need for integrated sexual and reproductive health and HIV. This clarity comes as the world nears the 2020 deadline UNAIDS has set for reducing new infections to fewer than 500,000 per year worldwide.

2020 is also the deadline for critical milestones in the contraceptive field. FP2020—the global partnership focused on tracking and expanding contraceptive coverage and choice—had hoped to see 120 million additional users of modern contraception (compared to 2012), and all projections say that target won't be met either.

Now what?

Click the graphic above to download. (All graphics from the Report available here.)

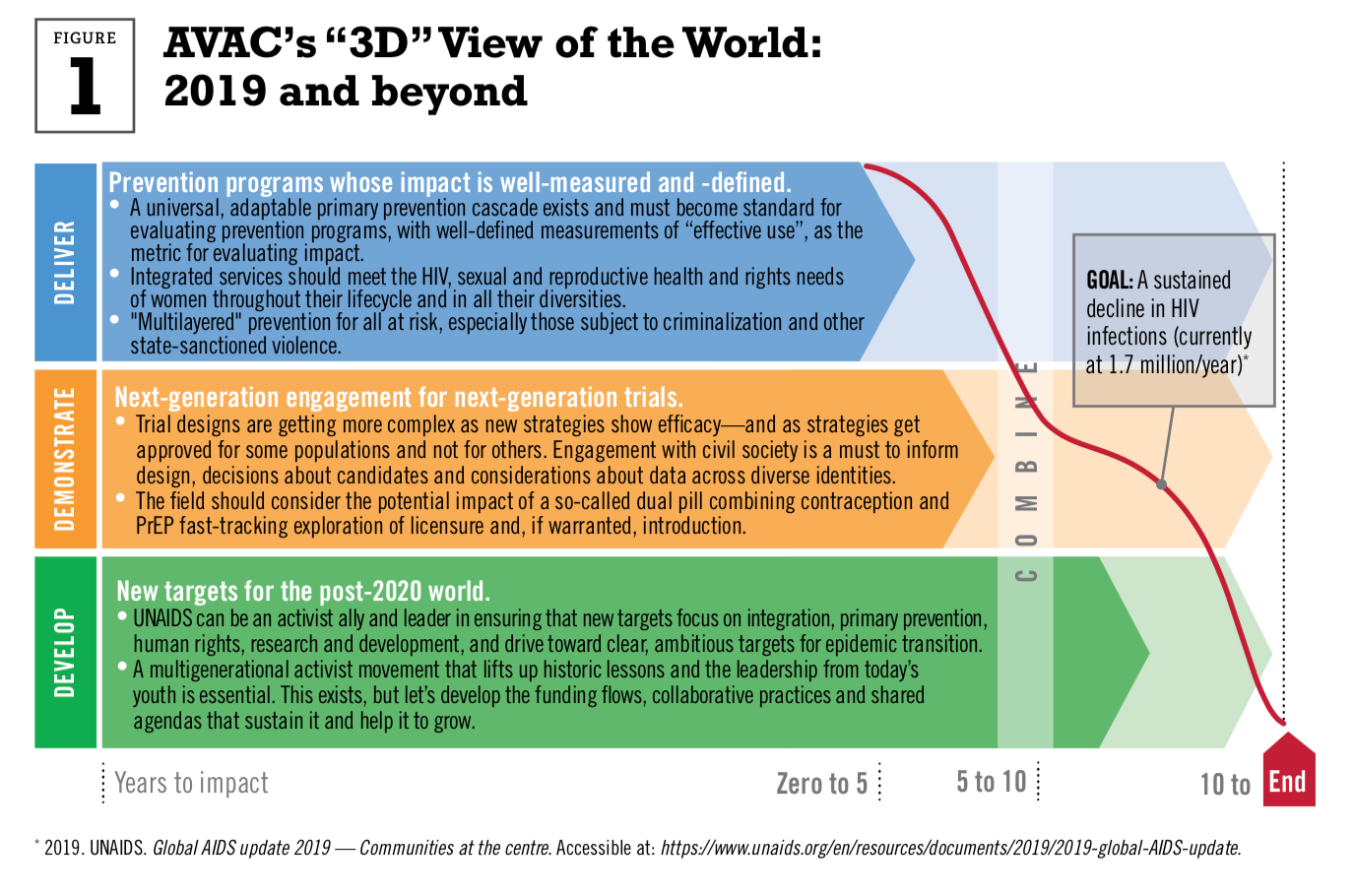

The answer that you'll find in this report is: sustain the investment, do the more difficult things that have been put off, measure those things, modify the approaches, repeat. It's easy to say, hard to do and there are unknowns at every step. But there is hope: much of what needs to be done involves approaches that are, in many respects, familiar. We need not reinvent the wheel, just reorient the direction of the field.

First: How exactly did this "Now what?" moment arrive? By way of research results. The best trials are not necessarily the ones that bring hoped-for conclusions. They are the ones that catalyze action—whether because of a positive finding or because the data drive home the need for action on an unsolved problem. This year, a set of studies brought problems with reducing incidence into sharp relief.

In July 2019, three major trials of universal test and treat (UTT) strategies presented results. They were, in a way, a test of the degree to which the test, treat and suppress targets—the most high-profile of the UNAIDS "Fast-Track Goals"—could drive down new HIV infections.

At an individual level, undectable viral load means zero transmission to sexual partners. Undetectable equals untransmissable (U=U)—along with PrEP—has the potential to change stigma, reduce or remove fear associated with sex, and shift conversations about HIV criminalization. This is undisputed. These trials sought to look at the population-level impact of ART as prevention.

Access to HIV treatment in rights-based programs that support people to start and stay on medication that suppresses the virus is a human right and an ethical imperative.

The International AIDS Conference in 2018 brought an early look at these data; one year later, the studies' results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The UTT strategies all achieved increases in population-level viral suppression over short time frames, with three of the four studies exceeding the UNAIDS target of 73 percent of people with HIV having undetectable viral load. In two of the four trials (Ya Tsie and PopART), this intervention package reduced HIV incidence relative to a control arm consisting of "business as usual"—meaning HIV testing, outreach and linkage to antiretroviral therapy all delivered according to national guidelines. There was no difference in HIV incidence between the arms in the SEARCH and TasP trials.

So is this good news, bad news or what? (Now what?) The first step to understanding what these trials show is understanding that they were markedly different in their designs.

Perhaps the most important difference between the trials is that all of the communities in SEARCH and TasP—the two trials that did not see a difference in incidence between the intervention and control arms—received universal testing at the start of the study. The SEARCH team has looked at its data and thinks that incidence went down by roughly 30 percent in both of its trial arms after roughly 90 percent of the communities received HIV testing, and saw major increased in virologic suppression among PLHIV. The two trials that offered universal testing only in the intervention arm saw reduced incidence in that arm compared to the control. Universal testing seems to have impacted incidence, in the context of expanded ART eligibility.

Click the graphic above to download. (All graphics from the Report available here.)

The message isn't to massage the data until you get what you want. It's that testing is critical, and community-wide approaches are a powerful tool for prevention and treatment. This runs counter to the current emphasis on index testing and the "yield" of HIV-positive people, and also has implications for rollout of self-testing. It suggests that a close look at the community-based research and rollout agenda for testing must be a top priority in the post-2020 epidemic response.

Across the trials and their differing approaches, the data were fairly consistent: over a three-year period, any approach that started with universal testing led to a roughly 20-30 percent drop in incidence compared to control arms without the testing push at the outset, in the context of rapidly expanding ART eligibility and high levels of uptake. It's likely that this incidence reduction would grow over time—three years is a very short timeframe for measuring epidemic shifts.

So yes, it is good news. But for much of the period that these trials happened, there were stakeholders who suggested that treatment as prevention could turn around the HIV epidemic. This includes UNAIDS, whose decision to launch Fast Track with the 90-90-90 targets alone (primary prevention targets followed roughly a year later) created the impression that meeting these treatment milestones would lead to "epidemic control". By the time UNAIDS began to highlight the unmet needs in primary prevention, the conflation of 90-90-90 and the end of AIDS was, in some places, complete.

These trials undo that conflation. They show what's possible and what still needs to be done with other strategies and by other means.

Let's be clear: access to HIV treatment in rights-based programs that support people to start and stay on medication that suppresses the virus is a human right and an ethical imperative. Also, a 30 percent incidence reduction is a substantial achievement. It's clear evidence that scaling up ART needs to be done, in its own right and as a part of effective prevention.

But 30 percent incidence reduction won't get countries, communities or the world to epidemic control or "transition". While there are places in the world where incidence is declining, there are no countries in which the decline has approached 75 percent. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, new diagnoses are skyrocketing.

Today, to be young, female, black and having sex in a high prevalence sub-Saharan setting is to be at risk of HIV and to be unlikely to remain in a PrEP program.

What's been done to date is inadequate. The number of young people in sub-Saharan Africa has increased dramatically—as it has worldwide. With such large numbers of youth, even with a modest decrease in incidence, the absolute numbers of new HIV infections in this age group will be similar to, or even larger than, annual rates earlier in the epidemic. Without prevention that fits into the lives of young people living with and at risk of HIV, there is no end to epidemic levels of new infections.

Another facet of this "Now what?" moment is the most recent research showing just how persistent these failures are for women, particularly young women in East and Southern Africa. In June 2019, the ECHO trial of contraception and HIV risk released its results. ECHO participants were not recruited on the basis of individual risk factors for HIV, meaning they were not asked about number of partners, engaging in sex work, history of STIs etc. Instead, ECHO simply enrolled women who were sexually active and seeking contraception in high prevalence settings. And yet, incidence amongst these women was 3.8 percent across the trial populations and reached as high as six percent in one of the trial sites in South Africa.

ECHO drove home the enormous unfinished business of meeting women's contraceptive and HIV needs at the same woman-centered service sites. Unfortunately, the response to the results from many quarters, was, essentially, "Phew, now there's no need to shift the approach to contraceptives."

The vibrant, African-led coalition of women's health advocates that AVAC collaborates with did not share this pure relief. In Section Three, you'll find our post-ECHO women's health agenda.

PrEP initiation in ECHO was quite low. And the information that has emerged from PrEP programs is that much more needs to be done for the strategy to fit into women's lives. At the IAS 2019 Conference in Mexico City, data from implementation projects aimed at encouraging adolescents to start and stay on daily oral PrEP showed that while many start, substantial numbers of them do not continue. This pattern isn't new, but the projects—which reflected the thoughtful youth-friendly and youth-led design of groups like the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation—were among the most innovative adolescent-focused efforts to date.

Today, to be young, female, black and having sex in a high prevalence sub-Saharan setting is to be at risk of HIV and to be unlikely to remain in a PrEP program. To be a gay or transgender person in Africa or the US—and many other places around the world—is to be at risk of being murdered, harrassed or physically violated at the hands of police. People who use drugs are criminalized, excluded from care, denied human rights and access to highly effective harm-reduction strategies. Authoritarianism is on the rise and that is bad for communities, public health and the planet.

Now what, indeed?

In the HIV field, it's time to face these additional realities:

• Much of what has been taken to scale are biomedical interventions implemented without the wraparound structural, social, cultural and political shifts that make it possible for people to use strategies to prevent and treat HIV.

• Multisectoral approaches that seek to reduce HIV risk and promote health by working at the level of education, economics, culture, rights and biomedical strategies are widely recognized to be essential for HIV prevention yet inconsistently programmed at scale. So is voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), which is still fighting for prevention funds even in the context of a concerted focus on "finding men".

• HIV prevention monitoring and evaluation has been steadily improving, but new insights aren't moving into widespread application, nor are they having impact quickly enough. The world has known for some time that incidence wasn't going down in all places, and groups like the Global Prevention Coalition and the HIV Modeling Consortium have, with UNAIDS, worked hard to define what to measure and what to aim for in the next set of goals. But that work hasn't moved from theory to practice. Countries can start to use current data systems today to estimate incidence reduction and assess, more directly, the impact of HIV prevention programs and investments.

If you look closely, that list of realities is also a list of solutions: the ones we've laid out on the next page.

This year's AVAC Report is written for everyone on the front lines of this fight who believes that curiosity and commitment will win the day so long as we're honest about what we know and what we don't, and so long as we listen to the answers that matter most, from the people most affected by and at risk of HIV. Together, we can and will answer the question, "Now what?"—not once, but again and again. With each honest answer, we can change the world.

Mitchell Warren

Executive Director, AVAC